Retro Barung

Retro Barung

By Mandy Lupton

In 2022, volunteer Peter Milton in collaboration with Megan Lee undertook the mammoth job of digitising the collection of Barung newsletters from 1994 – 2019. You can view the archive here (and please let us know if you have any of the newsletters we haven’t been able to source). As someone who is relatively new to the range, browsing the newsletters has given me a strong sense of the legacy that a committed group of staff, committee members, and volunteers have provided over an extended period.

Revisiting the Obi Obi Boardwalk Project – Looking back to Aug-Sept 1998

The spring 1998 newsletter features a front page celebrating the development of Obi Obi boardwalk revegetation project. This initiative was (and is) an iconic Barung project much loved by the community. As such it’s worth delving into the archives to track its progress. Newsletters in 1995-1996 reported on the design and completion of the project, including several community tree plantings.

The aerial images below demonstrate the change in the vegetation along the Obi boardwalk from 1958, 1993, 1998 and 2021. The 1958 image starkly illustrates the denuded landscape along the creek and within the town. The 1993 image is pre the boardwalk project but includes some planting undertaken in 1990-92 to enhance the showgrounds for the Maleny Folk Festival.

The Festival began in Maleny in 1987 and in 1994 having outgrown the site, moved to become the Woodford Folk Festival. The summer 1992 newsletter describes the history of the showgrounds Festival planting project, which was initiated by Festival Director Bill Hauritz in conjunction with Barung. When the Festival moved to Woodfordia, the planting tradition became ‘The Planting Festival’. Bill’s vision has thus provided a wonderful legacy for the Maleny Showgrounds and Woodfordia.

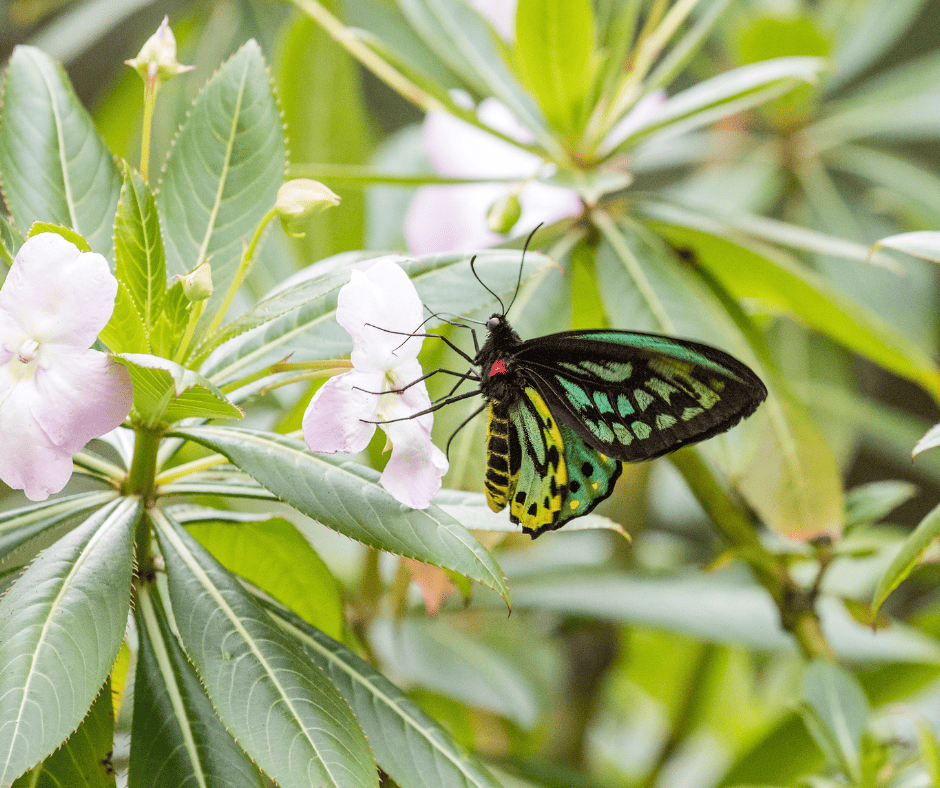

In the 1998 image, two years after the completion of the Obi Obi project, the boardwalk pathway is clearly seen. However, by 2021 the canopy is established and the width of the revegetation has increased. In the spring 1998 newsletter article the biodiversity of the emerging rainforest was celebrated:

Those who take regular strolls along the boardwalk are commenting already on the growth and development of the young trees and are beginning to see the forms which will emerge along the creek in the next few years. Water dragons, moorhens, black ducks, firetails, cormorants and echidnas are just a few of the regular wildlife tenants of the rainforest as it regenerates. Less frequently kingfisher or bar-shouldered kites may be seen on an overhanging branch waiting for a meal.

Previous newsletters indicate that improving the habitat of the endangered Mary River Cod was in part an impetus for the project, however, I am intrigued that the platypus isn’t mentioned, either in the rationale for the project or the description above. Is it possible that platypus were not seen in the creek at this time, and their numbers have only increased as the rainforest has matured and health of the Obi Obi has improved? In browsing the newsletters, the first time platypus is mentioned is in the Nov-Dec 1997 issue. In an extract from an academic article, saving platypus habitat is discussed in general terms rather than in relation to the Obi Obi. The point is made that ‘bank stability and aquatic food chain diversity are heavily dependent on riparian zone vegetation, thus the link between habitat quality and platypus status’. The Obi Obi and showgrounds riparian revegetation projects certainly deliver on platypus habitat in spades, much to the delight of current residents and visitors!

Thanks to Steve Swayne for help with the images.

TREE IN TIME

TREE IN TIME

We are introducing a photo competition in the newsletter where all entries go into a draw to win a prize.

To kick things off we would like members to send in a photo of themselves next to the largest tree that they have purchased and planted from the Barung Landcare nursery.

As a great example, here is a photo of Terry Boyle standing proudly next to a Silky Oak which was planted in July 1991.

Terry has been a member of Barung since 1989 and has done some inspirational revegetation work on his property at Bald Knob. If you would like to learn more about Terry’s work read his article ‘REFLECTIONS ON NEARLY 50 YEARS OF BUSH REGENERATION’ which you can find in the Feb 2023 Land For Wildlife, South East Queensland newsletter.

If you have a photo you would like to enter, please send your photo, along with a brief description including the species and date it was planted, to info@barunglandcare.org.au!

book review

book review

by Mandy Lupton

Grasses – Native & introduced grasses of the Noosa Biosphere Reserve & Surrounding Regions 2nd edition, 2009. By Sonia MacDonald & Stephanie Haslam

This book is a high quality production, featuring full A4 colour photos of 129 Poaceae specimens that have been pressed, dried, mounted and scanned. This mode of presentation reveals the sculptural beauty and fine botanical detail of each plant.

Each plate includes a brief description of grasses from the Noosa region and surrounding areas, including any extra details such as butterfly and bird habitat and suitability for pasture/fodder. The book presents as a scientific publication, focussing on identifying grasses rather than garden design. As a gardener, I would have liked to see a photo of each native grass in situ, rather than just the few examples provided. There is no information on the cultivation of grasses.

The book opens with chapters providing photos of some of the grasses in bushland, pasture and gardens. It provides a section on the structure of a grass plant, including close up photos of different types of inflorescence and reproductive parts. It covers native grasses in the first section, then presents introduced grasses.

Given the extensive research by Bruce Pascoe and others on growing and harvesting native grasses for human consumption, it’s disappointing that there is very little information on this topic. This is possibly due to the age of the edition (2009). There is just one mention of Indigenous use, and the terminology used – ‘Native Australians’ – is out-dated.

This book would appeal to those interested in the botanical features of local grasses. However, the A4 size of the book seems too large to be practical as a field guide.

member spotlight

Diana O’Connor

Why am I a seed collector?

When I ask myself this question my immediate thought is “because I love trees”.

Clearly there is a lot more to answering this question than that. Perhaps my next thought is “it is very late in the day for humans on this planet to make some reparation for our removal of forests”.

My mother was interested in botany when she was at school and I think I inherited an ability for plant recognition from her. We had a holiday shack in the bush in sandstone country north of Sydney when I was a child and that was my happy place. Hills with flowering Christmas bush and Hardenbergia (we called it Sarsaparilla), and koalas and possums and their strange calls in the night.

In Brisbane in the ‘80s I joined the Qld Naturalist Club and the Native Plant Society and began to learn parts of the local flora from members who were very knowledgeable, including David Hangar who ran the first rainforest plant nursery in the Brisbane area at Doolandella. Doing walks with people who know their plants is a great apprenticeship.

When we came to the Range in 2005, I learnt about the forests that had been largely cleared by logging in the 1900s. I was aware that an ecosystem needs a minimum of 30% remaining to be useful and hopefully survive. With the discovery of Barung Landcare Eric and I became involved on the committee. I learned about the activities of people doing plantings on their own blocks, their need to have plants available from local seed, the difficulties for Barung trying to keep itself afloat financially and how it relied on many volunteers giving their time and so on and so on. I began to volunteer at the nursery, with Wayne Webb tutoring me in seed preparation and sowing and identification of species. I became familiar with the reference books – there are many more than the “Red Book” now available. One of the easiest for beginners is “Mangroves to Mountains”. I gradually learned to identify various species and notice them in the landscape. I also became aware of the continual need for seed collection. I can’t really see how you would be able to pay someone for this as it is time consuming and often necessitates return visits to the mother trees.

I am fairly obsessive once I take on an activity that I have a passion for. I notice the weedy Privets as I pass them and I notice when I see a new tree in flower that I need to stop and identify (and later go back to see if they set fruit). At this stage of earth’s history, I feel that enabling our nursery to supply trees to locals who wish to revegetate their land is very important. You don’t have to be vegetarian for your life to be totally dependent on plants! Like our project replanting Rainforest in the park at Montville, seed collection is important for giving my life purpose in retirement. I don’t feel the earth owes me a free ride in my retirement years. We began our revegetation in the park at Montville in 2007. The group was about 15 or so to begin with and we have always met to work each week. Some have died, some were “forbidden” to come after turning 80 if they had big properties of their own to look after. Numbers are down to six at present, three of whom are originals and two of whom are older than 80! We have planted about 200 species largely sourced from Barung.

Seed collection often requires repeated trips to wait for fruits to ripen on a tree. It is possible to get permits for seed collection on council reserves but there are rather onerous rules which are discouraging even to us as committed individuals. We therefore check out the old residual trees that escaped felling in its heyday along the roadsides. This reduces the genetic diversity unfortunately and is a most unfortunate situation.

The Mary Cairncross plant list for Red soils has a category beside each species – common, occasional, rare and so on. One shrub was listed as very common in the reserve but I had never seen it available for purchase. One day I had discovered a tiny maroon flower and was photographing it in my ignorance when a man came down the track towards me. Instead of passing me he stopped. I mumbled that I didn’t know what it was when he told me it was Hedrainthera porphyropetala. This serendipitous meeting with Dr Robert Kooyman, one of the Grandfathers of Rainforest research in eastern Australia, had given me my “very common plant” in the flesh! Getting seed has had a horrible carbon footprint as finding fruits and trying to work out when they are ripe is almost impossible. They disappear from one visit to the next. We do not understand most of the beautiful and complex interactions in nature, so perhaps if this unremarkable shrub is common, it has a useful function in the system? Many trees do not fruit every year. Often, they fruit every second or third year or more. I need to keep an eye out to see what is happening.

You may not know of more than a few species near your place or on a morning walk but even collecting one or two species is a help. For the good genetic diversity required to make the new forest strong, a minimum of 20 “mother trees” is needed – research done in northern NSW. My seed collection falls far short of this – often one or two only. If more people collect from trees they know of – even one or two species, we will end up with better genetic diversity and this is very valuable for forest resilience. If you are not sure of the species take a short branch with leaves on and put it in a bag in the fridge till you can take it to the nursery for identification. Most rainforest fruits do best if soaked in water for 24 hours to drown any bugs that may be in them. Our nursery staff will be only too happy to guide you as to what each species needs.

The flora on the range varies with the type of soil they grow on. Barung has lists of the plants that grow on the various soils of the Range. You are much more likely to be planting a species that will fruit and persist in the landscape, if you plant what is native to that soil type. Get advice and you are much more likely to be doing long-term good. If we plant native plants in our gardens, we plant what local insects and therefore birds need to live and breed. Local insects have evolved with native plants. Small flowers and small bees for example. Birds need insects to feed to their young in the nest. Nectar and pollen don’t have enough protein. Honeyeaters and finches feed insects to their young. This is vital for successful breeding. So, you can have all the good layers we talk of for attracting birds to our gardens but if there are not enough insects, birds may visit but be unable to breed in your garden. That means they are functionally extinct in your garden. So, look after your insects!! Use poisons minimally if at all. Mulching your soil keeps it cool and moist and will make the dozens more critters in the top layers survive and improve the biodiversity and productivity of your soil and garden. If all the private landowners do this, we will be doing the best for the biodiversity of the land we are responsible for. If we can fit a tree on our block all to the good. There are many small ones available and tip pruning will keep them lower.

So, I urge you to consider collecting seed from your local trees. Our first responsibility is to the small area we live on so look after your soil and insects. Biodiversity will follow. Minimise your lawn. It has negligible biodiversity. Bush care groups do some great things and share knowledge so that is another way of helping locally and learning. We could do with a few more hands in Russell Family Park Montville on a Sunday morning if that appeals.

Contact me, Diana, on 0407029830 or turn up to the park to the hill behind the stone toilet block on a Sunday from 7am if you feel moved. In my experience it will give you more than you give it! Not to mention habitat for our fruit-pigeons.

Retro Barung

Retro Barung

book review

book review